Hello, My Friends! Salutations, Hola, etc.

Friday and Saturday I spent many rapturous hours working on my novel, the Apex Killers. I had been away from it for months, and digging back in is just fantastic for me. As I told Benita, I enjoy every stage of the writing process, from dashing out the first draft to repeated revisions working out every beat, filling in extra details and content, to polishing the manuscript as much as I can. Even formatting the book is enjoyable! This book has a lot of moving parts, so I’m probably going to hire an editor again to help me make sure I’ve covered everything. More on all this later.

Last week I wrote about the problems I’ve been having with my legs and feet. I’m happy to say that I’ve seen an orthopedic doctor, and he had a barrage of useful advice to help me get mobile again. For example, I’m wearing a compression sock on my left leg, and it has been heading off the excessive swelling. I’ve switched over to hiking boots, and they have offered me much greater support (and relief!) I even have some exercises that will help relieve the stress on my Achilles’ tendon. I was afraid I was going to have to undergo surgery and miss a great deal of work, or put off said surgery until I got vacation days to use for recovery and live in misery for half a year until those vacation days came back. Now I would like to think that I’ve reached the bottom, and now I’m ready for a significant turnaround in health. To better days!

Everyone knows that I’m a history nerd (my college degrees were in Medieval History and Creative Writing, as it turns out), Benita bought me some books on technology, masons and builders, clothes, and cloth dyes from the Middle Ages. This lady knows me! I’m one lucky guy.

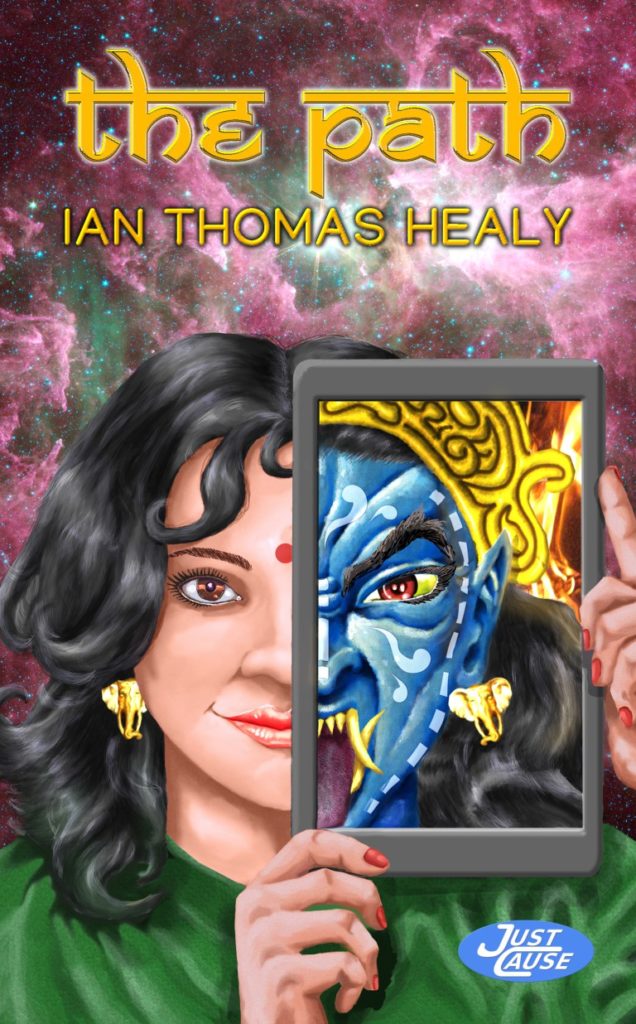

Here is the latest cover I’ve created for Local Hero Press:

Finally, here is an excerpt from a novel that I wrote a long time ago, and which I am now going to self-publish. I wrote this in pre-internet times, and try as I might I never found an agent or a publisher. Now is a different time, and self-publishing is a terrific option. The book is titled “Name of the Shadow,” and this is an excerpt from chapter one:

PART ONE, CHAPTER ONE

Raeth pounded the strip of smoldering white iron, alternately heating it over a small, pedal-blown forge and working it on a curiously shaped anvil. Satisfied, he pinned the iron to the anvil and then twisted it slightly with a pair of tongs. The tumbler, so intricate and precise, slowly came to life as he worked. He began tapping at it again, carefully now, with yet another hammer. Finally, he buried the tumbler in the glowing coals of the little forge. There, embedded in the red-hot coke, its impurities would slowly bake away, leaving steel where before there had been only iron.

Raeth enjoyed his work despite the rigors of his apprenticeship to Jhold Mendynn, the master locksmith. Raeth wanted so much more from life than a mere, “respectable” trade, but for now it would do. He was vain and well aware of his skill, which, for a boy of eleven, had already far outreached that of the other apprentices his age.

His master, oblivious to the merciless racket that Raeth raised below, lay unconscious in the little bedchamber above the shop. Raeth didn’t mind his master’s tardiness, though, for there were certain liberties to be had in being a drunkard’s apprentice. When sober, Jhold sharply criticized every aspect of Raeth’s craftsmanship, yet the old locksmith never failed to present it as his own work when dealing with customers.

In three year’s time, when Raeth completed his eight-year apprenticeship, he would be eligible for the status of full journeyman locksmith. Once certified, he then would be technically free of Jhold. The hard, economic truth, of course, was that once Raeth was a journeyman his status would change from Jhold’s ward, with its guaranteed food and lodging, to that of defenseless wage earner. As such, Jhold would owe Raeth nothing, and he would be more a slave than before, beholden to his master’s grudging generosity: Raeth could have his wages cut, be laid off in the slow times, or be fired.

Raeth preferred not to look at it that way, of course.

Once certified, he thought with a smile, I’ll be free of Jhold Mendynn forever–free to make my fortune in the world. Jhold can starve, for all I care, and, without me to carry his workload for him, he probably will!

Using iron tongs, Raeth pulled a nearly completed lock casing from the coals. It was black, yet in the shop’s dim light he could see the ruddy glow that emanated from within the metal. He plunged the casing into a small cask of fish oil, and it hissed in reply. Once polished, this piece would be complete, ready to house an intricate (and expensive) lock mechanism. In the empire of Aorlis, where skilled handiwork and ferrous metals both commanded high prices, true locks typically were reserved for members of the aristocracy, high churchmen, and the fabulously wealthy merchant princes.

From the street beyond, a shrill whistle cut the air. It was Murt’s standard rallying call, used to gather the gang. All prospective customers and ongoing projects were forgotten immediately, and Raeth, always ready for an adventure, closed down the locksmith’s shop in record time. Jhold, lying comatose above, would never know the better.

“Hey, Murt. What’s the news?” Raeth locked up the shop as he spoke, hanging the key around his neck by a thong.

The older boy, never quick to answer, regarded his Karmithian friend for a moment.

“Gang meeting. Everyone’ll be there. Come on.”

*

The port town of Enlith, capital city of Burlamshire, had been Raeth’s home all his life. He barely remembered his parents, for he was only six years old when they apprenticed him to Jhold the locksmith. That was the last time he ever saw them, for they never visited. Raeth grew up lonely, without parents or family, and Jhold took no other apprentices. As for Jhold, well . . .

Raeth found no parental substitute in his new master, only a cruel taskmaster and a grudging instructor. Raeth, in that innocent pragmatism unique to children, realized early on that his new master was a man bent on slow self-destruction; Jhold spent most of his evenings–and many of his days, too–fueling his depression with wine. He wasn’t young when he first took Raeth in, but now, due to the locksmith’s excesses, he appeared far older than his age warranted. It was Jhold who taught Raeth when to run, for the craftsman could be an abusive, angry drunk.

Still, Jhold had been an able teacher, through example if not instruction, and, when sober, a superb craftsman. Raeth learned quickly, and from the age of nine on he already was capable of many of the more sophisticated aspects of his craft, work typically reserved for full journeymen, not mere apprentices. Raeth felt challenged by intricate mechanisms of all sorts, and working with them came naturally to him. As Raeth’s skill and productivity grew, Jhold worked less and drank more.

When his duties were completed, or when Jhold was lost to the wine, Raeth would slip away and run wild with the local boys. Some of these lads, like Raeth, were derelict apprentices, while others were the children of the urban poor and laboring classes, the accidental sons of whores, or the orphaned children of sailors. Many of these boys were homeless, forced to fend for themselves or starve; these lived with the specter of death, and often were subject to the malnutrition, chronic illnesses, and parasites that were synonymous with life in large towns. For some of these children, the only means of survival was prostitution. (So precarious was this pursuit, however, that more than half of them ended up face down in the bay, their throats slit, half-eaten by wayward sharks.) Consequently, the roster of boys rotated regularly, and only the hardiest survived for long. Those rare few who survived to adulthood invariably became as tough as iron, bled free of the petty empathies that plagued most humans. These boys had a hungry gleam to their eyes, a feral light that promised little compromise.

The boys gathered in mobs, loosely knit bands that fed off the city. If Enlith were likened to a mouldy crust of bread, then the boys were the maggots, maggots who produced only flies. They vandalized, mugged, and practiced petty theft with near impudence, for in Enlith the law belonged only to those who could afford private armies or hired bodyguards. The boys, of course, were wise to the ways of the town and chose their victims carefully. They feared no one but rival gangs, and the intermittent gang wars that racked the port town were celebrations of sadistic desperation, fierce and bloody.

It was rough going for Raeth at first. He was born of Karmithian blood, but the other boys (like most of Enlith’s population) were born of Jotundgorn stock. The Jotuns were a tall, rawboned race of sea rovers; they were wild-eyed, red-bearded berserkers who made natural warriors. Karmithians, with their dark eyes and keen minds, were uncommon this far west in the empire. They were a small-boned, wiry people, easily tanned and darkly hirsute. They too made fine warriors, but theirs was an art of discipline, speed, and cleverness, not brute force.

Boys who are different have always been marked for the worst kinds of attention, but Raeth was a stubborn lad. His short lifetime of hard work, abuse, and loneliness had lent him a heart like iron and fists like boiled leather. He never backed down from a fight, no matter how badly he was outmatched. Consequently, it didn’t take long for tales of his spunk and sheer meanness to establish his place among the bigger boys. That, and Raeth’s swelling reputation as a poor looser, for he never admitted defeat, never gave up, and never gave in.

The “captain” of Raeth’s gang was a burly fifteen-year-old boy named Drak who had crooked teeth and dirty-blond hair that hung limply over his eyes. Drak remembered no parents and had survived all his days by his wits and meaty fists alone. His “first mate” was the taciturn Murt, a gangly youth who spoke little but was as rangy as a wolf.

Raeth’s initiation into the gang came when he tangled with Murt. It was a lost fight from the beginning, but one that Raeth was determined to win. Slowly, inexorably, the larger boy had pounded Raeth to within an inch of his life; the Karmithian boy called for no mercy, admitted no pain, and battled on long after his strength had failed him. Raeth had been a small nine year old, and Murt about thirteen and already quite formidable. Still, it was a noble defeat, and Raeth was part of the gang thereafter. It was a probationary membership, of course, because Captain Drak hated him; Raeth was a stupid Karmithian, after all, and not to be trusted.

As the months rolled by, Raeth roamed with the boys as often as he could. The climate varied little on the coast; generally, it was comfortably cool and humid, with a salty sea breeze blowing in by day, and a warm land breeze blowing back out to sea by night. Thus, the gang was active around the calendar. Raeth’s days, at least those when Jhold was sober, were spent at the locksmith’s shop, and most of his nights roving the streets.

Raeth’s popularity among the other boys grew steadily. He never refused a dare, and he cowered from none of their antics. He pelted off-duty soldiers with offal, swam beneath the piers on the bay, stole food from the market’s stands, and even knocked hidden holes in unguarded fishing boats. By now, most of the other boys conveniently overlooked Raeth’s cultural heritage and considered him a Jotun but for an accident of birth.

The underlying tension between Drak and Raeth never eased, however, and Drak’s practical jokes almost always centered on the Karmithian boy. As 1196 passed (Raeth’s second year in the gang), Drak grew taller, ganglier, and he even took to toting a fearsome meat hook that he’d stolen from a dockside warehouse’s salt lockers. If it were possible, Drak grew moodier as he matured. Now, when the gang’s captain called out his orders, his voice often cracked into a broken falsetto.

Drak was absent more often these days, and no one knew where he spent his time. In Drak’s absence, the remainder of the boys looked to Raeth and Murt for guidance. Drak and Murt now spoke little, and they were rumored to have had a falling out. Murt, despite his greater age and fighting build, now acted as Raeth’s unofficial second in command, just as Murt still sometimes did for Drak.

Some people, reflected Raeth, are born followers, just as others are born leaders.

As the year gasped its final breath, and old Chroneoss looked to his rebirth on New Year’s Day, Raeth came to believe that his position among the boys had nearly solidified–on the day he contested Drak for the captain’s “chair,” most of the guys would rally to Raeth’s banner. He was tough and agile, a true contender for Drak’s position. As the Karmithian boy saw it, Drak’s day had nearly reached its dusk, and the dawn of Raeth’s was fast approaching.